Time, Quality, & The Modern SFF Novel

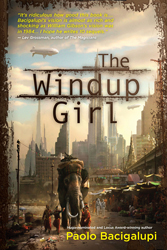

Yesterday, I referred readers to a number of interesting (I thought!) articles I’d read otherwhere in internet land. One of them was a two-part interview with Paolo Bacigalupi on the Orbit blog. One of the things that stuck with me in what he said, when speaking about his award-winning novel, The Windup Girl, was this:

“In the end, it took me about three years to write, not including the couple of years before where I’d been working out the world and writing short stories set there.”

“In the end, it took me about three years to write, not including the couple of years before where I’d been working out the world and writing short stories set there.”

You all know that I think The Windup Girl is an outstanding novel. And clearly a few other folk think so, too, because the awards its won include 2010 Hugo, Locus and Compton Crook Awards and the Nebula Award 2009, as well as being named as the ninth best fiction book of 2009 by TIME magazine. Awards aren’t everything, of course, but still—not bad going, huh?

But here’s the thing: what Bacigalupi said in the Orbit interview is that The Windup Girl took him between 3 – 5 years to write. Now there is no way that I can prove a correlation between time spent and quality, but there’s no doubt in my mind that The Windup Girl is a quality book. Equally clearly, it also took time to produce …

This has got me thinking, especially about today’s SFF writing world and the pressure to crank out a completed manuscript in 6 months to a year maximum. And although, once again, I cannot prove a correlation between timeframe and quality, I cannot help noticing several contemporary series where I have loved the first book and been bitterly disappointed with the second and third. I cannot help but wonder how much of this is because the first books are not written to such a tight timeframe, but the subsequent books are—and there just hasn’t been enough time to really get them right?

Effectively, what the 6-12 month standard timeframe means is that books are being treated like a production line item. But are they, really? After all, no matter how much the writer may strive to write to a formula, each plot is still at least slightly different, with some fresh problem to be resolved, and usually has to bring in some new characters as well. That’s just at the formula end of the spectrum. If an author does not wish to write formula, but rather seeks to try and create something really new with each book, then the going gets even tougher …

I think there is no question that time-to-market matters in our modern world. But what is the flip side of getting products to market quickly if in the end they disappoint readers? And if readers learn that the subsequent books in a series may often disappoint, what does that mean for the market in the medium to longer term? The whole thing about production line development after all, is the ability to replicate uniform design and achieve uniform quality—so if you can’t assure those two aspects through your process, then you’re not going to have a successful operation. So I think my conclusion is that books aren’t an industrial product and don’t suit that sort of model. And if they are an artisan product, where each item has some degree of uniqueness about it, then uniform time/production processes just aren’t going to work, certainly not all of the time—and are probably going to miss the quality/customer satisfaction target a lot of the time.

All food for thought, both as a reader and writer, even if I have no answers but only speculation to share—but from observation and experience, I cannot help feeling that it is no accident that an outstanding novel like The Windup Girl also took time in the making.

I’ve been thinking along the same lines recently. Doing a novel as part of a PHD has given me a 3 year timeline and a lot of extra tools for deepening the novel. I can’t know if it’s going to be better than my other fiction, but I have certainly sorted out a lot more of the potential problems, simply because I’ve had to take the time to do the extra thinking and research. it’s not true of al kinds of books, but I suspect that it’s very true of books like The Wind-Up Girl which have serious world-building needs. One thing that the author gets right in The Wind-Up Girl is the consequences of some of his assumptions and, for me, this means that he’s taken the time to think things through properly.

Certain novels can happen in six weeks, because they draw on emotions and on prior experience, but those novels that leave deep intellectual imprints are better for the time and consideration. Some writers write perfect prose and have balanced plots within a short time – others require revision and reconstruction and re-consideration. For me, that’s the bottom line. Writers are different, novels are different: a standard six months assumes that we’re all very similar. This short-changes readers, who are enjoying those differences.

Gillian—I had never thought of writing a novel as part of a PhD: what an exciting project! (But no, I still do not want to do a PhD.:) )

And I certainly wouldn’t want to say that a great novel can’t happen in 6 weeks or six months—that it must necessarily take years. But I know that it’s often on the second or third read through that I get the subleties of plot or character nuance—and to really get the benefit of going through a manuscript agiain, being able to come back to it after a break is a great bonus. I guess I’m your “revision, reconstruction, reconsideration” kind of gal (think: ‘tortoise’, very sadly, as opposed to ‘hare’!)—but even if I were a hare, I think the one-size-fits-all/production line model is always going to drive to ‘just get it out the door/rough enough is good enough’ type responses–and that will show up on the page. And end in disappointed readers.

That’s the bottom line, isn’t it – that readers get good books and that a production-driven model is going to interfere with the quality of a rather large chunk of those good books.

Gillian: that’s certainly the fear and I guess it’s my own disappointment with many next-in-series recently that led me to speculate.

I also think though, that there’s probably a point where there’s a positive nexus between the production and the creative ends of the model—where the need to deliver/publish can cut through the danger of what I referred to in another resposne as “endless iterations of revision.”

And here it’s a matter of the editor knowing the writer and working with him/her to achieve that perfect nexus point. It’s not an abstract “This should take six months for a perfect book by any writer” or “This is umpteen hours work” but “This is Writer A and this is this novel and this is its process.” There are definitely writers who work well with the current system and there are equally definitely writers who hurt from it. We’re not one size fits all.

Hear, hear, Gillian. And as a writer I think there can be some trial and error in finding your process, especially as the process changes quite radically once you get into the world of contracts and deadlines.

I can’t say that I share your enthusiasm for Windup; I’ve not been able to finish it. Can’t say why exactly, but my hindbrain says that I’m just not buying the world for some reason (and I also think it doesn’t like the style). I’m obviously not with the mainstream on this one and will take it on faith that it is a good, perhaps masterful, novel.

But regardless, the point I wanted to introduce in regards to your time/quality contention is this: everything about this so-called modern era, particularly in the fiction publishing realm, is mitigating towards churning out quantity rather than quality.

The whole ebook revolution contributes greatly; given the large number of (really, really bad) poor ‘indie’ ebooks I’ve glanced through that nevertheless receive high praise from a number of paying customers seems to indicate that there are two forces at work here: a younger reading public that is not as discerning and an economic model (not unique to publishing) that drives down costs, which in turn increases the pressure for volume.

If all ebooks hit that .99 to 1.99 holy grail pricing – what author could possibly keep up with the demand – without having quality suffer? What author would be able to churn out enough volumes in a year to keep the customers happy? Few, if any.

Wal*Mart, and what they do to suppliers, is just about a perfect model for the future: get the supplier dependent upon the large volume orders; then demand they cut their pricing (after all, there are plenty of your competitors who would love this business). Do it again next ordering cycle. And again. Finally, when the supplier is turning out barely acceptable crap and can’t cut any further, Wal*Mart dumps them in favor of another company that says it can meet the new, lower price. Maybe they really do have a more efficient, less expensive system that makes them more competitive, but chances are they’re just lowering the quality even further.

As ‘franchises’ increase their hold on the genre publishing world (easier and cheaper to market to a ‘captive’ audience; easier and cheaper to get an audience if it is tied to some other big property), there will be increased demand to feed the maw, quality will suffer and authors will get kicked off of their own creations because they just can’t keep up.

(Already happening btw.)

Authors may want to turn out quality work. The business world is not interested in anything other than – can they sell for a profit?

The future for quality is very bleak; readers are not demanding it in any demonstrable way (and are demanding swill by voting with their dollars), while at the same time the publishing world offers less expensive fodder because it is the only way they can keep their margins. All of the pressure is downwards towards crap.

Probably been a bad morning for me, lol, judging by the doom and gloom above.

Steve—in terms of The Windup Girl, I do love it, but there are reasons why this would “probably” be so given my predilections as a reader. I discussed some of these last year on the Harper Voyager blog when I “came clean” on my choices for the Hugo Awards. (It’s a longish post but does get to The Windup Girl in the end.)

In terms of your analysis of the market, although you may be having a bad mornng and feeling “doomy-y and gloom-y”, I can’t really disagree with your analysis. I am not sure of all the ins and outs of the industry (still a new writer, ay!) but common sense and reason suggest that your predictions are the logical outcome of the current situation. The irony that I perceive is that I hear a great many complaints about quality out there amongst readers—but often the same people are saying: “I won’t buy it if it costs more than .99 on my Kindle.” (Thus locking themselves into one supplier at the same time; i.e. I predict that if Amazon ever gets sufficient maret dominance the .99c ebook will not last.) I also know a great many people who won’t buy anything if they can get it for free and legally/illegally is not a great consideration for them.

I think writing has always been a business, but the pressures on that business are huge right now and the pressure to get ‘product’ out there and hope something strikes the right chord (a la ‘arry Potter & Twlight) correspondingly large. It is hard to see what the future holds for story as art/craft, but most of the discussions I have heard always seem to come back to some form of “patronage”, either via the public purse (e.g. the Dutch “artist’s stipend”) or the private—e.g. corporate sponsorship.

CJ Cherryh touched on this recently in her guest post on Night Bazaaar.com where she wrote that: “… My own theory is that it’s … [the future’s] … going to be far more like the Roman and Renaissance model—a handful of respected writers essentially distributing their own work, before all’s said and done. Modern literature came from that situation. And literature can thrive under those circumstances.”

It all sounds very nice, but the problem with the Roman / Renaissance model of the writing life was that one either had to be already independently wealthy in order to pursue writing, ie of the landed / leisured classes, or able to attract a patron. Both options effectively restricted creativity to a small, privileged handful (even smaller and more privileged than currently) and the patronage model also meant that the writer could not write anything that would offend his/her patron. So I see it as a somewhat limited model and not one we should necessarily be aspiring to see reinvented. But I fear that Cherryh may be right and the face of the future may indeed be fiction of indeterminate quality churned out for .99c an ebook (or less) while literature/writing of quality remains the preserve of the leisured/monied classes.

But then again, when I think back to the Victorian era of the “penny dreadful” and the serial novel, maybe it’s simply a case of “situation usual?”

All I can say is, hear hear. 😉 And I hasten to add, as someone who has had to deal with just such a rushed writing schedule: I know it can be done, but it ain’t easy, and in the long run it wears you down to the bone. I do think my second book trumps the first, even given the reduced time frame. But I paid for it with my health, unfortunately.

Mary, I agree with you that—although Tymon’s Flight is a good sound read—Samiha’s Song has that extra “something.” I suppose the question is—are there things about it, even an an already very good book, that you would have liked to have more time to work on? And I’m not talking endless iterations of revision, but serious aspects of the world, the characters or the plot? I am genuinely interested to hear by the way, not trying to grind any particular axe.

In terms of your comment that: “I paid for it with my health, unfortunately”—I feel that is a very damning indictment of the industry, especially as I know other writers who ‘off-the-record’ are suffering in exactly the same way. And why I think it is important that , as writers, we support each other in not locking ourselves into working in ways that are so detrimental to health and creativity. The corollary of that is that we also have to find ways of working that are economically viable: the proverbial bugbear.

I think ‘Samiha’ is more or less what it would have been anyway, given more time, but certainly I would have liked to polish and tweak the book further. There are still typos in the final product, which drives the obsessive editor in me nuts.

I’m on the record here, of course, but I hasten to add – I don’t blame anyone but myself for how things unfolded. I got into my contract with my eyes open, and did the best I could to make a quality product in the circumstances. And I’m an obsessive – always was, always will be. It’s clear I couldn’t be happy with half measures, so drove myself into the ground to deliver a book I could be proud of, no matter what.

Now that I have the experience under my belt… I’d do things differently. 🙂

Mary: I guess we all sign up for things we maybe shouldn’t do when we’re inexperienced, sure—but I can’t help but feel that one’s health is a very high price to pay for being inexperienced …

It is, I agree.

LOL See why I need editing time – I just used the phrase ‘hasten to add’ in two successive comments. *frowns editorially at self*

Mary, I think the two instances are sufficiently separated by other comments that you should not frown too harshly upon yourself.:)

I think a more useful measure would be the number of hours spent writing the novel.

For instance, say someone takes 200 hours to write a book. In one case, he puts in eight hours a day and finishes the book in about 25 days, just under a month.

Or he could only work on it an hour a day, which would take him 200 days or about seven months. The same number of hours is invested in both cases, but the timelines are significantly different.

So it would be interesting to me to compare the hours spent by authors you consider higher quality to the hours spent by more ‘factory production’ sorts. Is there a difference in the number of hours spent? How big a difference is it? Those sorts of questions seem much more useful to me. If we really want to find out what the link between time spent and quality is, anyway. Measuring by years without getting more specific just seems too vague and open to misinterpretation to me.

Then again, there are possible problems with measuring by hours too. Are conscious hours spent the most important thing to measure, or does some sort of work go on unconsciously as well? I don’t really know for sure, though I believe unconscious work does happen. If we’re focusing on conscious writing, though, I still think hours spent is a better measure than years.

But, then again… I think I’ve been struck by Anderson’s Law just now. Drat.

Douglas, I think the only true measure of quality is the final product—and given that Steve and I have had such different responses to The Windup Girl (and I have encountered this with other works of fiction, too) even that may be very much in the eye of the beholder!:)

I am only going to speak for my own experience here, but that has been, to date, that the longer the piece of work the more likely I am to need more time—more hours by your scenario—to get it to what I feel is a satisfactory standard where I am keeping faith with both myself and my readers.

So with flash fiction and poetry—bearing in mind that most of my poetry comes in within 40 lines—there are no considerations of i) sustained world building; ii) continuity and consequence of either science or magic systems; iii) plot and/or iv) character development that really need to be worked through. Flash and poetry tends to be more ‘slice-of-life’ writing in that respect. In terms of short fiction through to novelet length, some aspects of i)-iv) are usually present, but often there will only be one or two characters and a single plot thread to be worked through. So the structure is simpler and the issues to be worked through more straightforward, i.e. generally less “hours” required to get the work to the word “done.”

I’ve mentioned i) through iv) above, but perhaps I should take a step sideways and back here to say that, for me as both reader and writer, there are two aspects to enjoyment of a story, particularly one of book length. One is simply the idea and the power of the writing—and to be honest I think that can come fast or slow, depending on the writer and the way they create, and/or the power of the idea. The second—and the thing that will also spoil a great idea for me, no matter how interesting it is—comprises things like: plot holes I could drive a bus through; inconsistent character development; and/or only a few main characters are given any development at all, the rest are variations on the ‘cardboard cutout’; ‘fortuitous’ magic/science, i.e. it’s used as a ‘bandaid’ to cover holes in the plot; and characters behaving in ways that are not credible/believable in terms of the world and value set the author has established around them. There are a few more, but these are probably the ‘gist.’

So when I’m working on a book or series, where there is a consistent and believable world to be built; multiple plot lines to be kept running in parallel (and often with semi-visible threads that will (all going well) come out in later books); multiple point-of-view characters, and also major secondary characters, all with diverse motivations, I find that I do need a great a deal more time than on the flash fiction, or even the novelet. This time can be in actual hours spent working on the manuscript, particularly reviewing and revising, but also allowing for “down time” between “on-manuscript” sessions, i.e. for ideas to percolate and gel and my subconscious to make certain things conscious. (These eureka moments usually go something like “oh no, that won’t work because …”, or “this character would never behave like that, so you’ll have to find another reason for him/her to be or do whatever they’re meant to be doing or being for the plot to work—or be prepared to change the plot.” Etcetera …) The other vital element of time, I believe, is that needed to gain external feedback from critical readers. This is a vital part of my manuscript development process and so I need to build in enough time for it to happen.

I certainly don’t think quality of outcome can be reduced to a formula in terms of time. Some people work faster than others; some people are telling more straightforward stories, others more complex—these will all drive to different outcomes in terms of time. But the original speculation driving my post was that I don’t think writing can be a “one size fits all” system in terms of timeframe, however much that does seem to be a feature of the current business model. And I do think it can—although not always, with a result to my good friend Mary Victoria and Samiha’s Song—result in disappointing outcomes with subsequent books in series.

At the end of the day, effort in does not necessarily equal quality out—but assuming a modicum of talent, an ‘idea’ and effort paid to i) through iv), at least I know that I’ve done my very best to assure a good product. And given the story its best shot at a start in the world. If it does not ‘take’, for whatever reason, I never want it to be because I’ve shortchanged the creative process.

Thanks for explaining your views. I’m always curious about the methods of other writers. I agree that the final product is the only true measure, though as you suggest different people measure it differently.

I seem to be much more a ‘seat of the pants’ writer than you are. In the past I’ve tried going over a story again and again, fiddling with things, but such work drives me batty. For me it’s most enjoyable writing the first draft, making something new. Then I do some clean-up of things like spelling and so forth. But I leave the plot structure and things like that alone. For me, fiddling with that stuff is just too big of a time sink, and I’m never sure what I’m doing is even making the story better. Instead, I just write something new again. I trust that I (consciously and unconsciously) will get better with practice.

Douglas, I think it is always good to hear how others do things—but we are all very different and have to find out what works best for us. And I don’t rule out the ‘sit-down-and-dash-off-the-masterpiece’ possibility, in fact I’ve written several short stories and parts of novels where very little changes occurs on the re-read. But the faster I write, ie the more inspired I am, the more I find that typos and repetition in particular ‘pepper’ the first cut, so getting the idea out there is vital but for me, the re-read and revision stage is vital, too. But that’s ‘just me.’:)