© Helen Lowe

Runner Up, New Zealand Society of Authors (Auckland) Short Story Competition

2006

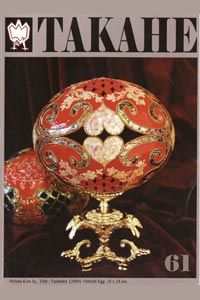

Published Takahe 61, July 2007

In those days, the railway stopped at Tapu, which boasted a small dairy factory and a sawmill. Anyone who wanted to carry on to the Spit, with the shallow waters of the Inlet on one side, and the southern ocean crashing in on the other, had to either hire transport from Tapu, or walk. Most of the summer people walked, staggering out with packs on their backs, or shifting a case from hand to hand - or there was Peg.

Peg was a local fixture by the time we spent our first summer at the Spit. She would bring her wheelbarrow to meet the train, and you could pay her to push your bags out to the baches. She met the train on our first day, a tall, gaunt woman pushing a wheelbarrow with no tyres on the metal wheels. My mother felt sorry for her, and let her take some of our bags, but I think she regretted it when Peg started cursing the sand and gravel ruts that passed for a road. I was shocked, but delighted, and followed her often after that, just to listen to the language. All the children did, creeping along in the lupins beside the track.

She always knew we were there, and she used to talk to us whenever she stopped for her "breather". She would turn her back on the southerly and blow smoke towards the Inlet, ranting on about her " 'barrer", life on the Spit, and the garden she was making, out behind the patchwork of packing crates and old iron that she called her crib.

The ocean beach was the other place I saw her, still with the wheelbarrow, which she would fill with stones. She strode along the water margin like some long legged wading bird, but always kept clear of the breakers. She yelled at me when I ran to play in the creaming foam, a stream of words torn away by the wind, but I understood that she was warning me off. I thought I must have intruded on her domain, but later, on one of those many trudges back from the train, she told me it was a "drownin' beach", and that I should keep well away from the sea.

"Takes everythin' that ocean," she said, squinting through the cloud from her cigarette, "animals, folk, ships - drowns 'em deep. So you keep clear, hear?"

It was a wild stretch of coast, with the sea pounding in on a beach that was all stone. There was no softness to it. There were a few baches on the ocean side, but most were built along the sheltered Inlet. It was safe to swim in the water there, or make castles along the sandy ribbon of beach. I ran and shrieked with the other children, while my mother sat on the dunes above, under the shade of her Japanese umbrella.

Peg admired that umbrella. She would stop the wheelbarrow to tell Mother so, with only a mild curse for emphasis, if she passed our gate or we met her on the Spit. My mother would always answer, usually just a word or two about the weather, or how Peg's garden was progressing. Peg told her it was to be Japanese as well, and made of stone, like a picture she had seen once, in a book.

We didn't live in the baches, but in what had been the pilot's house when scows and coastal traders came across the bar, into the Inlet. It stood, creamy as a shell, where the Inlet beach curved into a small headland, and you could hear the ocean roaring on the other side. Mother and I had come to the Spit for the entire summer, but my father joined us on the weekends, catching the train out from town. He never let Peg wheel his bags though. He called her an appalling woman, and said she should be locked up.

"I think she was, once," Mother said. She paused by a window, watching the sunset turn the Inlet red. "She told me there was a fire, and she had to smash through a barred window to get out."

My father grunted. "She must be strong, then."

"Yes." Mother turned away. "Most of the women didn't get out. They were burned alive. I think I remember reading about it in the newspaper, at the time. But Peg escaped, and walked away in the confusion."

"And came here?" My father was concentrating on lighting his pipe. "Someone should've reported her, got her sent back."

"She doesn't do any harm." My mother drifted to the other window, picked up a cushion and plumped it, put it down again. "And she's useful, carrying bags in her 'barrer, as she calls it."

My father liked people to be useful.

"She's building a garden," I said, "out of rocks. That's why she goes to the beach with her wheelbarrow."

Mother smiled, but my father was frowning. "I don't want you going anywhere near her," he said. "She's dirty and foul mouthed, and she could be violent."

Mother shook her head at me, cautioning silence. "None of the children go there, John. Peg talks to them, or at them, whenever their paths cross, that's all. It's the same with everyone. But there's no harm in her," she repeated, "and she's quite clean, just a bit rough."

My father harrumphed, but let the matter drop. It was the weekend, he said, and he wanted to relax, not argue about some mad woman with a wheelbarrow. And I don't think he ever did anything about Peg. The locals said, when we came out again the following summer, that it had been the new doctor at Tapu. He was a young man, and zealous, not one for live and let live. He too found Peg appalling, and thought she should be locked up. He made the necessary calls, and the hospital sent two male nurses out on the train. A policeman came too, from the station at Rivermouth, further down the line.

We were told that she hit out like a man and ran like an Olympic athlete. They had to chase her all the way out to the Spit, and by the time her pursuers reached the beach, she was already in the ocean. She had filled her pockets with stones and walked out, and the fierce rip did the rest. No-one tried a rescue; you didn't, on that coast.

Not long after that, someone burned her crib. It was just a few charred pieces of wood and iron when we returned, but the garden was still there. The gravel wasn't raked smooth anymore, but you could see the boulders, set like rocks in a river. My mother showed me how Peg had laid out the smaller stones to reflect constellations in the night sky.

"I helped her with this one," she said. "It was the day before we left, when I gave her the umbrella. Can you see the pattern? It's meant to be the Pleiades, when their rising marks the Maori New Year."

I said nothing. Above us, a seagull cried invective on the wind. After a moment, Mother reached out with her foot and knocked the stones aside.