Feeling For Daylight: The Photographs of Jack Adamson

Yesterday I attended the opening of the exhibition, “Feeling For Daylight: the Jack Adamson Collection” at South Canterbury Museum. The opening also included the launch of the book, Feeling for Daylight: The Photographs of Jack Adamson, written by Rhian Gallagher.

My connection to the launch and the book was through knowing Rhian—you may recall that I featured her poem, Between, as my June 29 Tuesday Poem. Rhian is a poet with a background in the publishing industry and first encountered the photographs of Jack Adamson when she returned to South Canterbury in 2006, after 18 years living and working in London. The collection of around 450 glass photographic plates, glass nitrate negatives, and also some of Adamson’s camera gear had recently been denoted to the museum by the Adamson family—and when Rhian saw the plates and learned the basic facts of who and what Jack Adamson was, her first response was: “there’s a story in this”.

Having seen the exhibition yesterday and had my first look at the book, I can only agree: Jack Adamson’s life and work definitely comprise a story that deserved to be told. I am very glad that Rhian, together with the curatorial team from the museum, found the time and funding to do so.

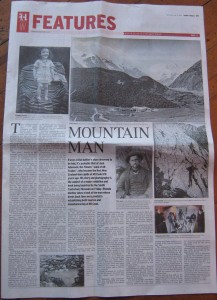

Jack Adamson was born in Timaru, South Canterbury in ca. 1868, the son of working class, farming parents who had immigrated to New Zealand from Scotland. The book focuses on the time when he lived at the Hermitage, in the Hooker valley at the foot of Aoraki-Mt Cook, which is New Zealand’s highest peak. During that time, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jack Adamson became one of New Zealand’s first alpine guides and was instrumental, with his wife Nora, in keeping the Hermitage going as an early destination for New Zealand’s fledgling tourism industry and mountain climbing tradition.

But the interest of the collection, the exhibition and the book, is centred on Jack Adamson’s marvellous photographic legacy. What struck me about these stark, powerful, black and white images, is not just the historical record they provide of climbing, climbers and the Mt Cook region, but also their wonderful humanity. These photographs capture people as well as place: climbers, station workers, swaggers, Jack himself and also his family–and not in the stiff, formal way so familiar from most Victorian photographs. What distinguishes these photographs, for me, is their naturalism, redolent of modern photographic approaches. The images caught in the photographs become real people, their eyes and expressions still speaking to us eloquently, despite the separation of more than a century.

A wonderful project and a wonderful book: my sincere congratulations to Rhian and everyone involved with the project.

If you get the opportunity, see the exhibition; if you can’t do that and are at all interested in photography, mountain climbing, mountain guiding, and/or NZ history—or know someone else who is—you should definitely consider buying this book.