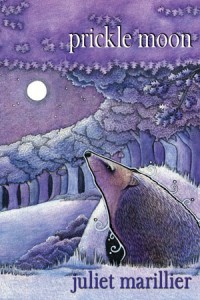

Just Arrived: “Prickle Moon” by Juliet Marillier

I sometimes think “…there is nothing, absolutely nothing, half so…” much fun as receiving new books in the post!

I sometimes think “…there is nothing, absolutely nothing, half so…” much fun as receiving new books in the post!

Last week’s book fun was an advanced review copy of Juliet Marillier’s first short story collection, Prickle Moon, which is due for release in April (2013) from Ticonderoga Press.

The book contains 14 tales, many previously published but 5 written specifically for this collection, including the eponymous Prickle Moon.

One of the previously published stories is Juggling Silver, which you may recall I featured as part of my A Peek Inside Tales for Canterbury series, here. Lovers of Ms Marillier’s Sevenwaters series will also be pleased to find the novelette, “‘Twixt Twilight And Water” in the collection.

Prickle Moon has already received a very positive review from Publisher’s Weekly: click here to read — early review.

As a taster, here’s that excerpt from Juggling Silver again:

—

from Juggling Silver

by Juliet Marillier

“Grandmother kept her silver plates in a row on a high shelf. They sat there looking down at us like three round eyes. Every day she took them off the shelf and polished them with a soft, red cloth, and then she put them carefully back. If we climbed up, we could see our faces in them. Ulli climbed up a lot.

“Ulli, Ulli, what are we going to do with you?” Grandmother would say. “Eight years old and never out of trouble! Eight years old and still babbling baby talk! Get down off there before you break something!”

The plates were very old and very valuable. They had belonged to Grandmother’s great-great-grandmother. On the rims of them were silver berries and leaves, owls and wolves, whales and dolphins. Grandmother called them the tree plate, the eye plate and the sea plate. Sometimes she let me hold them.

“Careful, Sami! That’s treasure you have in your hands!” She never let Ulli hold them.

Ulli was different.The other boys and girls his age ran around and played with a ball. They hunted for shells and went swimming in the rock pools. They helped their mothers to salt fish and gave their fathers a hand with tarring boats or untangling nets. I could talk to them and they’d understand me. Not Ulli. My little brother wasn’t safe on the beach by himself. He’d just walk into the water and keep on going. I’d waded in and fished him out hundreds of times. Ulli didn’t understand what people told him. And he couldn’t talk, not the way other folk talked. All he would say was a sort of rhyme, over and over, in words that didn’t make any sense: tipi api sipi oh, tipi api sipi oh. He’d sit on the bottom step outside Grandmother’s hut and play with a little pile of round, black stones, throwing them up in the air and catching them one, two, three, and all the time he’d be saying it, tipi api sipi. There was no point yelling, “Stop it!” Words meant nothing to my brother. Grandmother said Ulli would never be able to cast a net or paddle a canoe, not even when he grew up. All he would ever do was talk nonsense and juggle stones and get into trouble. It was just as well he had me to watch over him. Taking care of Ulli was my job.”