A Guest Post by Rowena Cory Daniells: “Fantasy, the Poor Cousin of Science Fiction”

Introduction:

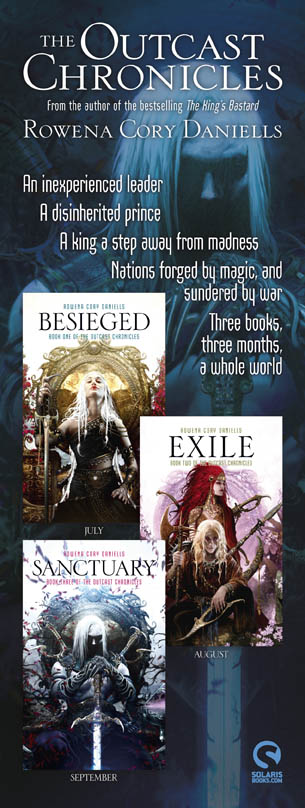

I have been hearing the name of Rowena Cory Daniells for some time now, as one of the exciting new authors of speculative fiction to emerge out of Australia over the past few years. The Chronicles of King Rolen’s Kin was released in 2010. Her new trilogy The Outcast Chronicles (Solaris) is being published in August, September and October of this year.

I have been hearing the name of Rowena Cory Daniells for some time now, as one of the exciting new authors of speculative fiction to emerge out of Australia over the past few years. The Chronicles of King Rolen’s Kin was released in 2010. Her new trilogy The Outcast Chronicles (Solaris) is being published in August, September and October of this year.

But Rowena is no newcomer to speculative fiction: she has been actively involved since 1976 when she jointly set up small press publisher Cory and Collins, as well as being involved with the Aurealis Awards and the establishment of Fantastic Queensland.

You can find out more about both Rowena and her new trilogy, The Outcast Chronicles, below her guest post. But right now I am absolutely delighted to welcome Rowena to “…on Anything, Really” to share her thoughts on “Fantasy, the Poor Cousin of Science Fiction.”

—

“Fantasy, the Poor Cousin of Science Fiction”

by Rowena Cory Daniells

It is time fantasy was rehabilitated as a genre?

I attended a literary event recently. When a librarian heard I was a fantasy writer, she said: ‘Oh, fantasy, that’s the sort of book you feel guilty reading. You know it’s bad for you, but you read it anyway.’ She went on to talk about readers who turn up at the library and have read all of the Wheel of Time and are looking for more series they can devour. She was referring to the big fat High Fantasy books, so loved by readers.

I attended a literary event recently. When a librarian heard I was a fantasy writer, she said: ‘Oh, fantasy, that’s the sort of book you feel guilty reading. You know it’s bad for you, but you read it anyway.’ She went on to talk about readers who turn up at the library and have read all of the Wheel of Time and are looking for more series they can devour. She was referring to the big fat High Fantasy books, so loved by readers.

And so despised by reviewers.

Everyone has heard the China Mieville quote: ‘Tolkien is the wen on the arse of fantasy literature. His oeuvre is massive and contagious… He wrote that the function of fantasy was ‘consolation’, thereby making it an article of policy that a fantasy writer should mollycoddle the reader (Miéville, PanMacmillan).’ *

It should be said here that in the past if you were a writer, (with a publisher who was willing to publish your books) you wrote what the publisher contracted you to write and High Fantasy sells.

Nowadays, you can self publish and reach an audience. It may not be large, but there will be someone out there who likes your stories. Or you may strike a chord with readers and word of mouth will turn your book into a best seller. So the range of fantasy books available and the blurring of the genres is marching on at a great rate. Even back before technology opened publishing to the masses, people like Mieville (Perdido Street Station, 2000) and VanderMeer (City of Saints and Madmen: The Book of Ambergris 2001) were pushing the boundaries of fantasy.

Nowadays, you can self publish and reach an audience. It may not be large, but there will be someone out there who likes your stories. Or you may strike a chord with readers and word of mouth will turn your book into a best seller. So the range of fantasy books available and the blurring of the genres is marching on at a great rate. Even back before technology opened publishing to the masses, people like Mieville (Perdido Street Station, 2000) and VanderMeer (City of Saints and Madmen: The Book of Ambergris 2001) were pushing the boundaries of fantasy.

Mieville did his PhD thesis on “Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law.” In an interview in Believer Mag he says: ‘I’m not a leftist trying to smuggle in my evil message by the nefarious means of fantasy novels. I’m a science fiction and fantasy geek. I love this stuff. And when I write my novels, I’m not writing them to make political points. I’m writing them because I passionately love monsters and the weird and horror stories and strange situations and surrealism, and what I want to do is communicate that. But, because I come at this with a political perspective, the world that I’m creating is embedded with many of the concerns that I have. But I never let them get in the way of the monsters.’

While Mieville sets out to entertain, the issues that concern him naturally creep into his work. Writing a book is a long process. The writer has to be passionate about the characters and their dilemmas.

I read somewhere that the role of the artist is to hold a mirror to the world so that we can see ourselves more clearly. Sometimes there are truths we don’t want to see, even when they are presented in fiction. The strength of the science fiction genre is that it can hold a distorted mirror to the world and through this we can see more clearly because we are distanced from that which disturbs us. I believe the fantasy genre can also serve as a distorted mirror to help us see ourselves.

I read somewhere that the role of the artist is to hold a mirror to the world so that we can see ourselves more clearly. Sometimes there are truths we don’t want to see, even when they are presented in fiction. The strength of the science fiction genre is that it can hold a distorted mirror to the world and through this we can see more clearly because we are distanced from that which disturbs us. I believe the fantasy genre can also serve as a distorted mirror to help us see ourselves.

Anyone who has read Terry Pratchett will agree this is what makes his books so powerful. Even as you laugh, you are groaning because his observations are so accurate.

Back in the 70s, when I had my book store, I discovered Fritz Leiber. I read everything of his I could find. One of Leiber’s Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories has stuck with me, thirty years later. It appeared in “Swords in the Mist” and was called Lean Times in Lankhmar. Out of work and down on their luck, our two intrepid heroes have to take steady jobs. The Mouser becomes hired muscle for a thug, who shakes down priests. (What is delightful here is that the Mouser puts on a bit of weight and acquires a little pot belly that rests on his thighs when he squats down. I love this touch of humanity). Meanwhile, Fafhrd becomes an acolyte of an obscure god known as Issek of the Jug. Due to Fafhrd’s musical training, the god acquires a following and starts making money, which leads to conflict with the Mouser. The ending had me laughing aloud. It was a scalding commentary on organised religion.

Another writer whose books remain vivid in my mind is Mervyn Peake. His Gormenghast trilogy was so obsessively detailed that even now, when I catch myself slipping into obsessive details I think: ‘I’m getting a bit Gormenghast.’

What these authors have done is use the fantasy genre to comment on society. This is what I’ve tried to do in The Outcast Chronicles. It is still a ripping read, because I love a good story. I like to put my characters in situations that test them as people. And I can do this in fantasy because I build my secondary world specifically designed to test them.

What these authors have done is use the fantasy genre to comment on society. This is what I’ve tried to do in The Outcast Chronicles. It is still a ripping read, because I love a good story. I like to put my characters in situations that test them as people. And I can do this in fantasy because I build my secondary world specifically designed to test them.

So I think it is time to embrace fantasy. It doesn’t have to be a guilty read. Let’s just enjoy the genre.

—

(Disclaimer, I have not read every fantasy book ever written so I am sure to have missed some of your favourite).

*See an analysis of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies with Tolkien’s books here.

—

About Rowena Cory Daniells:

Rowena Cory Daniells has been involved in speculative fiction since 1976 she set up the small press publishing house Cory and Collins with Paul Collins. Working as Paul’s assistant gave her an insight into the travails of Independant Press publication and a great respect for anyone who does it. Since then she has run a bookshop, then a graphic art studio where she illustrated children’s books, and had 6 children in 10 years. Then she sold nearly 30 children’s books and a fantasy trilogy. Her latest fantasy trilogy is with Solaris. With her husband, Daryl, she works in R&D Studios.

Rowena likes to support the writing community so has served on the management committees of Romance Writers of Australia, the Queensland Writers Centre, and the Brisbane Writers Festival. She was one of the founders of Fantastic Queensland (FQ) which runs Clarion South, and served on the Aurealis Awards for five years. She has established a national genre award, and set up national workshops and pitching opportunities, as well as running workshops on writing at national SF conventions, schools and libraries, and World Con 1999.

Together with Marianne de Pierres, she was a founding member of the VISION writing group which went on to form Fantastic Queensland. She and Marianne also formed ROR, the national critiquing group.

Rowena lives by the bay in Brisbane, with her husband and six children. She has studied the martial arts Tae Kwon Do, Aikido and Iaido, the art of the Samurai sword.

She has a Masters in Arts (Research) and received a Distinction in Drama Screen Writing unit through Griffith UNI. Currently, she is an Associate Lecturer at Qantm College.

To find out more about Rowena and her work you can check out her website, here, and her blog, here.

—

About The Outcast Chronicles:

About The Outcast Chronicles:

This series follows the fate of a tribe of mystics, the T’Enatuath. Vastly outnumbered by people without magical abilities, the mystics are persecuted because ordinary people fear their gifts.

This persecution culminates in a bloody pogrom sanctioned by the King who lays siege to the Celestial City, last bastion of the T’Enatuath.

A fantasy-family saga, the characters are linked by blood, love and vows as they struggle with misplaced loyalties, over-riding ambition and hidden secrets which could destroy them. Some make desperate alliances only to suffer betrayal from those they trust, and some discover great personal strength in times of adversity.

The first novel, Beseiged, is out this month, with Exile and Sanctuary following in September and October respectively.

To view the trailer, click here:

Interesting article, but I’m not sure if it does address the title as I was expecting a sort of compare/contrast rather than a look at Fantasy through the years. Expectations are a pain!

As I remarked to Helen earlier, I think fantasy is definitely becoming a strong contender when put up against science-fiction. Shows like the late-and-lamented-yet-terrible Camelot, Game of Thrones, Merlin etc are definitely bringing it back in style, bigger and better than ever. As several other people have remarked in recent times, it is now “cool to be a geek” and that “we geeks have had our victory over the jocks, because they now want to be us”. Somewhat disparaging yes, but I think it is an accurate description of things.

We are in another phase where being a geek is fun, it is “hip”, and where it is BIG. Superhero movies these days dominate movies and summer release schedules. Fantasy TV shows are taking over television networks. Comics publishers are turning more and more to the “mystical” and “magical”, and even redesigning some classic fantasies such as the new Grimm Tales comics.

Where books are concerned, I think both SF and F are rather balanced, although it does feel at times that SF titles don’t get as much exposure as fantasy titles. Maybe it has to do with the awards for the latter being much more prominent? I don’t know. It’s a feeling I get.

There’s also the feeling that fantasy has more avenues of exploration to exploit, compared to SF. Steampunk, vampires, dark fantasy are all rather popular these days. SF-y steampunk not so much I find. And thieves and assassins are also proving to be VERY popular. SF… that true space opera feel of the years past is not quite there. And most SF tends to be rather near future than far future. We are looking much more closer in that respect to much further off. Maybe that’s a result of us finally catching up to some of the oldest and most iconic facets of SF: lasers, satellites, extraterrestrial explorations, deep space mining, commercial space flights and so on.

I’ve definitely been reading a lot of fantasy this year because it’s largely a genre that I had invariably stopped reading a while back. TBH, I’d more or less stopped reading all that much until quite recently.

I don’t know. My thoughts are disjointed too!

You’re right, Abhinav, fantasy is more accessible than a lot of recent SF.

Fifty years ago, SF was the upbeat genre about a golden future. The Star Trek 1960s series is an example of this.

SF explored the big ideas, while fantasy looked backwards to a medieval past that never really existed. That was the way the two genres were seen.

Hi Abhinav, I don’t find your thoughts at all disjointed and I do understand what you mean, because I share your perception that in terms of current popularity, Science Fiction is possibly becoming the poor relation of Fantasy: a different thesis than Rowena’s, but I did mention this in my interview on Civilian Reader a while back. Stefan asked my opinion of the genre today and I observed that: “Probably I can point to the Harry Potter and Twilight phenomena (you rightly mention ‘A Game of Thrones’ as well) bringing FSF far more into the mainstream, and although paranormal fantasy set in a contemporary urban milieu is not new, the huge upsurge in paranormal urban fantasy/romance definitely is. I also have this perception that far fewer science fiction novels, and certainly hard Sci-Fi stories, are being published and the current trend favours Fantasy subgenres. (I do not know whether hard data supports my perception or not.)”

More recently, in my valedictory for Ray Bradbury, I wrote that “…I cannot think of any writer currently who is putting out anything encompassing the same depth and breadth of ideas…” This is not disagreeing with Rowena: I certainly think Fantasy is and should be capable of exploring big ideas, but I don’t think a great deal of either SF or Fantasy currently being written is doing so, not in the way that Bradbury and many of the classic SF greats did. For me, SF is/ideally could be all about the marvel of “What If?”, the sort of excitement and hopefulness and wonder I feel when watching “with bated breath” for the Curiosity lander’s successful touch down. But like you, I see most of the SF focus of recent years being on near future dystopia, an expression of our fears around climate change, peak oil (and worse–peak chocolate!) and an uncertain future, eg The Windup Girl, Oryx and Creyke, The Road. Even The Hunger Games spins dystopia not only out of the uncertain future, but also our current fetish for ‘reality tv.’ (Although of course the origins of the ‘tributes’ concept is very old, at least as old as Theseus and the Minotaur.)

I also think you’re right to assert that the love for antiheroes and lovable rogues has switched from the swashbuckling era of space opera to contemporary fantasy. I feel that the more adventurous (as opposed to romantic) steampunk is currently the ‘natural successor’ to space opera for those kind of stories. (Girl Genius, anyone?) While noting that Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser were of course both lovable rogues and firmly ensconced in a more classic epic storytelling.

So I think that, in terms of popularity, SF may well be more the poor relation than Fantasy, but in terms of respectability—which was of course Rowena’s opening thesis—with authors like Atwood and McCarthy writing what is effectively science fiction, however much they may deny it, there is no question in my mind: SF is still far more respectable in a mainstream sense. And although I believe you are also quite correct in pointing out that geekdom is becoming downright popular, and possibly even fashionable (quelle horreur!), that is not at all the same thing as being respectable—or not quite yet, anyway. 😉

I don’t think that you can really compare the two genres as if they are monolithic “blocs”, with one being inherently more powerful, or more valid than the other.

How do you compare a work like Peter F Hamilton’s “Reality Dysfunction” series with “The Game Of Thrones” and say that one is inherently better than other, just because it chose a different intellectual vehicle for story telling?

Both genres are flexible and diverse – too flexible and diverse to ever fit a label of poor cousin on to one or the other.

Hi Andrew,

In the past SF used to get the reviews which praised it for exploring big ideas, where as fantasy, especially the quest fantasies, were looked down on. That was where I was coming from with the title for the blog post.

I was saying that fantasy can tackle big ideas.

Between you and Abinhav, I realise I didn’t give enough background.

Hi Andrew, I suspect Rowena’s point is that people do, though–like the librarian’s comment that opens the post. Although I do agree with you: it’s not the genre that gives the storytelling merit, it’s what the author delivers in that genre by way of quality of writing, depth of characters and plot, ideas and themes. So the question becomes not: “is it an orange (SF) or an apple (Fantasy?) but is it a magnificent example of either an orange or an apple… And then there are those books where I feel, quite strongly, that it is not about genre at all: regardless of genre, this is a great book!

Hear hear! Or is it Here here! I’ve never been sure…

Anyway I second that, Helen.

‘So the question becomes not: “is it an orange (SF) or an apple (Fantasy?) but is it a magnificent example of either an orange or an apple… And then there are those books where I feel, quite strongly, that it is not about genre at all: regardless of genre, this is a great book!’

Am pretty sure it’s “Hear, hear…” 😉

Isn’t it the case, though, that anyone who doesn’t read a specific “genre” tends to dismiss it, whether that is science fiction, fantasy, romance, or, mystery & detective.

That being said, I think that any genre has it fair share of stinkers. What is that law that says a certain percentage of anything is usually dross?

Perhaps, being human, we most like to dismiss what we do not know? But I think you are right about any style of fiction having its dreadful as well as excellent examples — or such has been my experience. But I’d also agree with Zireaux, in line with my own comment about good books, that the elements that make the book or story ‘good’ or ‘bad’ are usually not to do with the genre but with the writing.

Fence, the genre that gets the most snide remarks is Romance. Yet, it is the only genre where a mid-list author can make a living.

Next would come fantasy, I think. At least some SF books are regarded as literature, eg. 1984

I’m with Zireaux in holding that it’s all literature and also believe that it is the quality of the writing that should be all, but am aware that various ‘powers that be’ may not agree. For example, Creative New Zealand lists the forms of literature it is “interested” in supporting and am fairly certain that I’m correct in recollecting that it excludes most forms of literature that might be categorised as “genre”, with the exception of that which also falls under the umbrella of YA.

For the moment, Fantasy is winning. If you lump steampunk into the fantasy side, its even more starkly visible. At the “box office”, so to speak, fantasy is outdoing science fiction.

Granted, its currently Urban Fantasy that has superiority over the rest of the subgenres of F/SF, but there is plenty of epic fantasy out these days. Science Fiction? Not as much.

I think SF started to slip in the popularity stakes when the writers began writing those really bleak futures.

Maybe the books needed to be written, but people want to be uplifted, especially when the current times are challenging.

Although I guess the times are always challenging to the people who live through them!

I’m not sure I agree about the bleak futures, Rowena, because there’s plenty of really brutal/bleak Fantasy being written as well. I think that may be many reasons but I wonder if one of them might not be that real science has outstripped the fictional so it is harder to speculate successfully? But that doesn’t explain the demise of space opera so much, ie the fantastic in space…

Do you have a view on why that is, Paul?

Why is Fantasy ascendant over SF?

Well, its not because of dystopian SF, this trend has been happening longer than dystopian SF has been popular. But both come from the same source–the state of the world.

Since 2001, the future that seems to be ahead of us in the real world has gotten progressively darker, grittier and less appealing. It’s bee more difficult to come up with an appealing future for SF. While SF is not predictive, the starting conditions have been more and more bleak to work with.

As a result, you get two trends:

1. Dystopian SF, since your initial conditions keep implying that is the future.

2. Fantasy: The way out of the trap, a la the Kobyashi Maru, is to change the rules. Add magic. It can be magic in the real world, which is the simplest solution (UF), or secondary world fantasy.

The other factor why UF is ascendant is that this reflects demographics in the genre community–more female readers, and female readers coming into the genre from paranormal romance.

Paul said: ‘Since 2001, the future that seems to be ahead of us in the real world has gotten progressively darker, grittier and less appealing. It’s bee more difficult to come up with an appealing future for SF. While SF is not predictive, the starting conditions have been more and more bleak to work with.’

I’d say the ‘I’m in love with a technological future’ type SF stories were really big from the 30s through to the 60s. Everything was upbeat after the 2nd world War, true there was the threat of Nuclear War, but life for the average person was better than it had ever been. Technology was going to cure disease, take us into space and create a Brave New world.

I passed a group of seniors out on an excursion yesterday and I heard two of them say ‘We grew up and raised our families in a Golden Age. I’d hate to be young today.’

Then society changed. The Vietenam War, Watergate, Greed is Good. People became disillusioned and this was reflected in popular culture.

The fantasy books of this period offered a glimpse of an idealised past.

Fantasy has been growing grittier in the last 10 – 15 years (I’ve done a post on this which has yet to go up). It’s probably a number of factors: the roll on effects of terrorism where war knows no boundaries and, more recently, the root cause of the GFC. But it could also be that a larger proportion of readers have reached a level of sophistication where they want more challenging fantasy reads.

Once you know a genre really well, you start looking for books that push the genre. Writers have been writing these kind of books, and you could find them coming from Indie Press but big publishers react to market forces. With the success of Joe Abercrombie, the major publishers will look favourably on gritty fantasy books.

Feel like I’ve rambled here. Hope it makes sense.

Plenty of sense, Rowena. In terms of gritty, it’s hard to go past the huge success of George RR Martin and the A Song of Ice and Fire series as well—although I think the antiheoric trend has much earlier origins, with Michael Moorcock and Elric for example, as well as Glen Cook’s The Black Company.

Hi Paul, My intuitive ‘take’ on this (no data, so strictly holding my finger up to test wind direction here) is to agree with most of what you say–except… There’s always an “except”, no? 🙂

In this case, the premise about bleakness does not hold so well, I feel, if one applies it to space opera. That is effectively “fantasy in space” but has been fading at much the same rate as more science based predictive SF (with the exception of dystopia.) So I feel there has to be something more going on here. It may simply be that space is now too ‘real’ for us to suspend disbelief sufficiently for the “wormhole magic” to happen, but at face value there should still be more of a place for space opera.

My second exception relates to your closing statement, ie the implication that SF has declined because of “more female readers” coming into the genre, specifically from paranormal romance. I do take exception to this Paul, for several reasons. One, the paranormal romance phenomenon is of very recent provenance (the reasons why a whole post in themselves) really the last 5 and no more than the last 10 years absolute maximum to my perception. The decline of SF and corresponding rise of Fantasy goes back a lot further than that—I would see its beginning around the mid 1980’s but really hitting its straps with the Wheel of Time series et al in the early to mid 90s. And in terms of the huge popularity of WoT, ASIAF, and Steven Erikson’s Malazan series, I would strongly aver that you cannot hold the ladies accountable for that, Paul—certainly not solely responsible at any rate.

As for female readership and SF — I love good SF and have done so since my early teens and I know a great many equally longtime female readers of SF who feel exactly the same. We would love to see more and read more, just as much as the blokes would—but it just ain’t there. And going back to earlier remarks—I don’t believe it is either right or fair to lay that at the door of women’s presence in the SFF genre reading market.

“Just sayin’ “:)

I feel the hook in my cheek — and that, too, when I know I’ve swallowed a similar debate before! (Only to end up flailing on dry ground in the end).

But still, for a few paragraphs, I must leap and splash and make a mighty spectacle of myself.

Tackling big ideas? Do we really wish for any book to attempt such a thing? You mention Bradbury. In my childhood I read and admired everything he wrote. I also fell under the spell of romance novels (H.G. Wells), science fiction (Jules Verne), what you want so desperately to brand “fantasy” (Tolkien) and so forth; but the book which most captivated me in my early youth — even, I can say, transformed me as a writer — was Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine. A beautiful novel about nostalgia and boyhood, with nary a robot nor monster anywhere in its liquid summer warmth.

Which demonstrates my point: For what is Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream but fantasy fiction? What is The Tempest? What is Kafka’s Metamorphosis? What is Bradbury but a writer of literature? Before E.T. phoned home from Hollywood, the great Bengali writer and film director, Satyajit Ray — best known for his intense character dramas — wrote a story about an extra terrestrial befriending a young Indian child; and I seem to remember a Jurassic creature making a cameo in one of his children’s stories as well.

Fact is, artists transcend genre, because genre is their ruin.

And just as a good book doesn’t adorn its fleshy form in genre (I prefer my literature in the nude), it doesn’t “tackle big ideas” either. Nor should it. A good book is an intoxicating mix of beauty, imagination, craft and longevity — like the dandelion wine of Ray’s childhood. I think what your librarian is getting at, Rowena, is what might be called an “escapist genre.” That is, the fantasy novel as cruise ship, as floating shopping mall, the book which keeps you well-fed and well-entertained while visiting some far off Wonder-of-the-World, or which happily docks beside a scenic jungle, a jungle you never penetrate, with natives you never meet. (These, by the way, were the books enjoyed by — and which may have fatally doomed — Anna Karenin).

Zireaux, firstly, lovely to see you here again: I always welcome your contribution.:) And although I love big ideas wherever I find them, including my fiction–although they are not a prerequisite for my enjoying a story–so would say yes to your first question, at least from time to time. But as for the rest of your comemnts: I agree 100%. “What he said–and so eloquently–hear, hear!’ I would only add that I suspect we will never escape discussions of genre, however, no matter how much we may seek as artists to transcend, simply because as human beings we love to categorise: it’s a kind of shorthand for living life, alas.

Zireaux, I love this line: ‘A beautiful novel about nostalgia and boyhood, with nary a robot nor monster anywhere in its liquid summer warmth.’

Nothing wrong with taking a cruise. We all need a break now and then, just as we don’t always want to eat only steak. Sorry about mixing my metaphors.

A good book is a good book, no matter what the genre. I’ve always said this about children’s books. Yet, children’s authors are often asked, when are you going to write real book? (As in a book for grown ups).

And re “Yet, children’s authors are often asked, when are you going to write real book? (As in a book for grown ups)” I always feel that is the ultimate in condescension …

Yes, I think it was Jane Yolen the US YA author who said you never ask a paediatrician when are they going to become a real doctor and operate on adults!

I remember doing a workshop with well-known NZ author Joy Cowley in which she went through all the things an author needed to consider when writing an effective children’s picture book—and thinking: “Wow, that’s really hard. I would find that seriously challenging.”