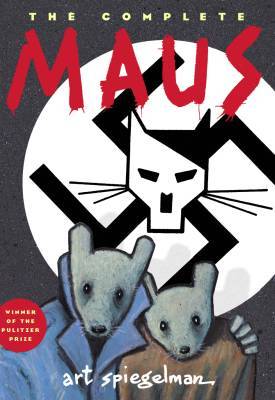

Recommended Reading: “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

A big part of “wot I do” here on “…Anything, Really” is read and share m’thoughts on books I’ve enjoyed reading. Usually this is a pretty easy process, but I felt the stakes were higher with Maus, because of the controversy around it being removed from the Eighth Grade reading curriculum by a school board in Tennessee, USA. The reasons cited, I believe, were “content” and “age appropriateness.”

In the interests of avoiding knee-jerk reactions, I wanted to take my time over reading the book and penning this post. As noted when it arrived, I do believe it’s essential that we read such works for ourselves and form our own views around their merit, rather than relying on the opines of others.

Having said that, the complete Maus (comprising volume one, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History and volume 2, And Here My Troubles Began) was awarded the Pulitzer Prize (the Special Award in Letters) in 1992, which I do give considerable weight when considering the opines of others. 🙂

Nonetheless, having read and reflected, my view is that Maus is a profound, deeply moving, and thought provoking work of literature.

What Maus Is About

What follows is not a synopsis, for the simple reason that I think it’s impossible to encapsulate Maus. I really believe it’s a work that one can only experience firsthand. In very broad terms, however, Maus is about the experience of the Spiegelman family, and particularly of the author’s father, Vladek Speigelman, during the precursor to the Nazi invasion of their Polish homeland in WW2, through the invasion and subsequent Holocaust, and into the aftermath of the war.

The events of WW2 are juxtaposed with Vladek’s final years in America, as seen through the lens of his son, Art, who is conducting a series of interviews with him. The interviews were undertaken with a view to creating the cartoon, or graphic novel, that became Maus.

Maus: The Creative Motif

Maus is a graphic novel, i.e. a narrative of some length and complexity, told in cartoon format, which I believe contributes to its narrative power. The central creative motif comprises the various nationalities caught up in WW2 being portrayed in animal guise: specifically, with heads and faces in animal guise; the rest of the character’s body is drawn as human.

So, the Jews are mice (hence Maus); the Poles, pigs; the Germans, cats; the Americans are dogs, the Swedes reindeer; and the artist/author’s French wife is initially depicted as a frog. There are other depictions, but these are the main ones.

There is a logical flaw in what I’ve just written, though, which you may have spotted. I spoke of nationalities, when in fact the Spiegelman family were Polish by nationality, Jews by religion. Similarly, when in the USA, they are American by nationality, and again, Jews by religion. So although almost all the other guises are nationalities, that of “mouse” reflects a religious group within nationalities—which I guess is what Hitler and the Nazi regime did. A particular religion, the Jews, were singled out from the rest of their nationalities, whether German, Polish, French et al, and persecuted as a separate people.

Describing that process, and the human suffering involved, is central to Maus, which may be why Art Spiegelman chose a quote from Adolf Hitler as its epigraph:

“The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.”

The narrative that follows, in my humble opinion, consistently and repeatedly underlines the extent to which Hitler was wrong: the Jewish people in Maus are entirely human, reflecting the full and varied “sorts and conditions” of humanity, and therefore, being fully human, cannot be a species apart.

Returning to the central creative motif of animal guises, I would also describe it as a self-aware motif. At times, the mouse guise is clearly drawn as a mask over the underlying nationality of Pole, French person, and so on. While at the beginning of Maus II, And Here my Troubles Begin (which starts with chapter one, Mauschwitz, so you get the picture), the author discusses “how he should draw her” with his French wife, Francoise.

Why I Think Maus Is A Profound Work of Literature

Although I have read and viewed a great many fiction and non-fiction works relating to the Holocaust, Maus still stands out for me. Yet a work can be moving because of its subject matter, without necessarily being great literature

The reasons I believe Maus not only stands out but is literature, is because of the power of the graphic format, the weight of the subject matter, and the subtlety and nuance involved in crafting the narrative, which works at several levels.

At one, it’s the story of Vladek’s wartime experience and a portrait of him as a survivor, as told through his responses to the interview questions posed by Art. In this sense the story, although based on lived historical events, is also personal and episodic. The narrative moves back and forward in time, between Vladek’s wartime experiences, including Auschwitz and Dachau, and the end-of-life interviews with Art.

It’s also very much an account of how survival has shaped Vladek and Art’s mother, Anja (who committed suicide in 1968), as well as Vladek’s second wife, Mala, and Art himself, as the child of two survivors.

It’s also a story about what survival means, and the emotional reactions and judgments attached to it, including those the survivors themselves—for example, guilt, shame, and despair—as well as the judgments of others.

Most of all, it’s a story of the relationship between a father and son, with all the normal challenges and difficulties where the father and son are very different personalities, compounded by the Holocaust—with Art always trying to determine how much of what shapes and distorts the relationship is “just his father”, and how much is the Holocaust legacy.

Unquestionably, Art has a difficult relationship with Vladek, and this is one axis of the Maus story. The other, I believe, is Vladek’s devotion to his wife, Anja, and determination to hold onto their relationship and be reunited with her. Tellingly, it is their reunion that marks the culmination of the book: the winning through of love (I will not say “triumph”, given all they’ve endured and still have to face together) in the face of darkness, hardship, and loss—which should be unimaginable, but isn’t, because we have very clear records of exactly what occurred. So we do not need to imagine: we know.

Although the Holocaust story is one of horrors, the narrative’s juxtaposition of past and present grounds the reader in hope, by showing Vladek’s survival and a brighter future—one in which there is room for family dynamics and differences. So at the other end of the book, but also through the book, we see Art’s fraught relationship with Vladek, but also his love and admiration: Maus is testament to it.

My view that Maus is a profound work of literature is not solely because of its subject matter, or the way in which the past is interrogated through the lens of Art’s relationship with his father in the present. The graphic format also contains and confines the horror. It’s a very spare form of storytelling because so much of the narrative is contained in the images: for example, when we see the mouse guise as a mask, and when it’s integral to the character. For all their starkness, the events are sparely told: this is Vladek’s experience and recounted in his words—including any observations and interpretations, which tend to be confined to the events themselves, rather than animadverting on a larger picture.

Nonetheless, as readers we understand very clearly what the larger picture is. The narrative reveals it very clearly, through the effects of events on the characters. Yet despite those effects, the story’s greatest achievement is that it is not a story of hatred, but of great humanity and of love: qualities that shine through the book, and together with its straightforwardness and the power of the graphic format, make Maus a compelling work. It’s a book I won’t readily forget.

Nonetheless, there are several moments and lines that stand out. One is Art’s conversation with his “shrink”, Pavel, who is also a Holocaust survivor. Art is speaking of his struggle with writing Maus, as well as his struggles with his father. The conversation turns to survival, and whether it is admirable to survive and therefore, conversely, victims should be blamed. Pavel concludes, re surviving the Holocaust, that:

“…Life always takes the side of life, and somehow the victims are blamed. But it wasn’t the BEST people who survived, nor did the best ones die. It was RANDOM!”

Vladek’s experience, as related through Maus, supports that view.

The second moment comes close to the end, when Art discovers family photographs and is looking through them with Vladek. So many photographs, yet only three in Anja’s (Art’s mother’s) family survived the Holocaust, and two in Vladek’s—including Anja and Vladek themselves. The rest, from the very old to the very young, were all gone.

Conclusion

I believe Maus is a great book; I recommend it unreservedly.

In terms of matters of content and age appropriateness for high school age readers, I don’t believe there is anything inappropriate in the content—and again note that it is compelling work of great humanity and love.

Maus also illuminates a period in history, one I believe it’s important we all know of, and understand. Works like Maus provide an important means of accessing that knowledge and understanding. In a high school curriculum context I would expect works to be read with teacher guidance, with the degree of guidance depending on the age of the students.

I studied 1930s Germany and WW2, including the Holocaust, twice while at High School, once at age 13-14, and again as a more senior student. I don’t believe there is anything in Maus that’s unsuitable for high school readers in either age group. I also read many works of equivalent emotional and subject-matter complexity independently during those years—without, I like to think, any noticeable ill effects, then or since. 😀

~*~

For the Record: I purchased my copy the complete Maus, which is a paperback edition, published by Penguin, 296 pages.

I have not read Maus, but it’s been on my list for a while, and I will try to get to it soon. The book banning and censorship that is going on now in our “enlightened” year of 2022 is awful and egregious, and books like this are more important than ever.

Thank you, Helen, for this insightful review!

Thank you, Beth, for your thoughtful comment. Having read Maus, I could identify no grounds whatsoever for it banning it, so “egregious” seems a very apt term.

I read Maus many years ago now, and then again recently.

It is an incredibly human story, in both the worst and best sense.

You know the facts of the holocaust, but the personal scale of the story makes the reading experience immersive and immediate. And powerful. And unique

I couldn’t agree more with your summary, Andrew. Thank you for commenting.